There are two things that should be beyond question. First, that Australia’s common language is English. Second, the inherent value of our English language is that it gives us the ability and freedom to communicate with depth and full understanding.

Without that ability, messages conveyed or received can become rather murky or misinterpreted. There’s also the risk that directives or reforms are not fulfilled, or not sufficiently questioned to determine their merit or intent.

Digital education is a case in point.

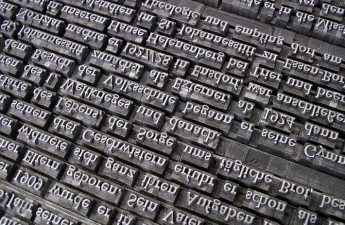

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Digital Education Revolution (DER) in Australia. It was a $2.2 billion project, aimed at, ‘changing teaching and learning in Australian schools, to prepare students for further education and training; and to live and work in a digital world’.

We post, we ‘like’, we tweet, we abbreviate.

In 2011, a survey was conducted to identify the success of this project. Of 9,435 schools, just 175 schools, or 0.018%, responded. These schools were encouraged by ‘changes in students’ access and use of computer engagement, and preparation for a digital world’.

In stating it was ‘changing teaching and learning in Australian schools’, was the DER aware of historically poor response rates by schools, and therefore also aware there would be little, if any, evidence of revolt from schools with regard to the DER?

When the DER was introduced, 90% of Australian schools reported a computer:student ratio of worse than 1:2, justifying the investment in providing one computer for every student in Years 9–12. Seven years later, 25% of WA schools acknowledged their devices were more than four years old. Maintaining state-of-the-art digital access, via purchase or lease, would now be up to parents in WA, and all other parents across the nation.

In stating that it was ‘preparing students for further education and training,’ did the DER really mean its investment was temporary, and that parents would become the major investors in digital communication?

Today, digital devises includes cell phones and tablets. Continuous access to information, whether accurate or otherwise, is the new social currency. Moment-in-time monitoring and reporting is the new school currency.

We post, we ‘like’, we tweet, we abbreviate. Every time we share a post or selfie, we believe we are popular, socially engaged beings.

In stating that it was ‘changing teaching and learning to prepare students to live and work in a digital world,’ did the DER realise that competency in the English language would be compromised by the ‘monitoring’ of peers and the ‘reporting in’ of each and every one of our own movements?

Every time we share a post or selfie, we believe we are popular, socially engaged beings.

Could it be that the Digital Education Revolution has been a greater success than was ever hoped for (or feared)? Have the ability and freedom to use language been compromised? Have we, in fact, been the engineers of a self-inflicted digital incarceration?

Copyright © 2018 Cheryl Lacey All rights reserved.

Parent, educationist and advocate of agitating change in Australian education. By raising the bar we can face any global challenges facing Australia and Australians.

Click here to learn how we can work together or contact me at cheryl@cheryllacey.com.